Shrunken Heads for Inflated Egos

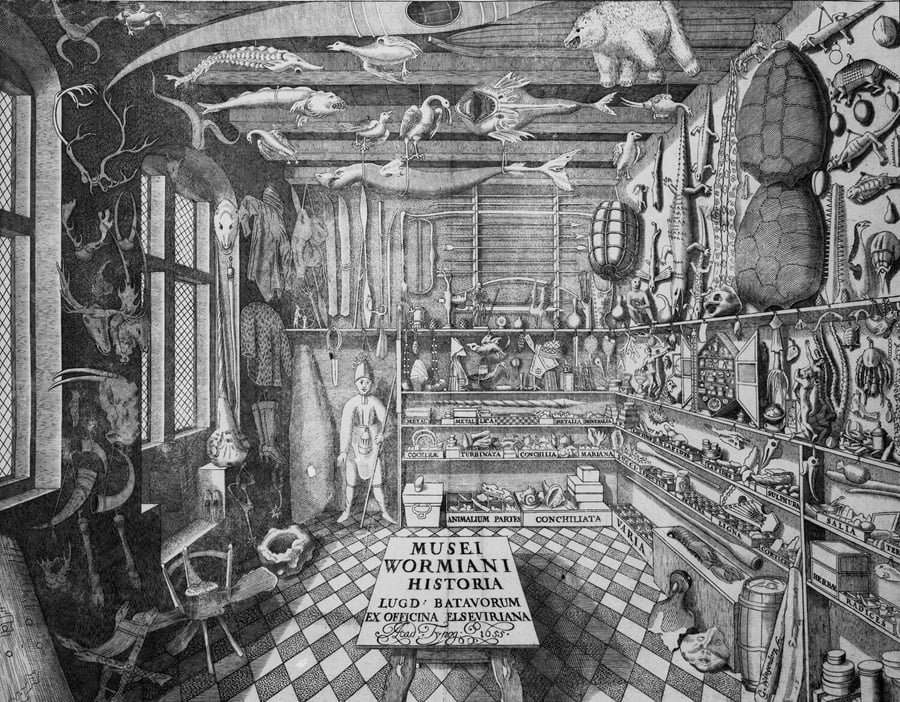

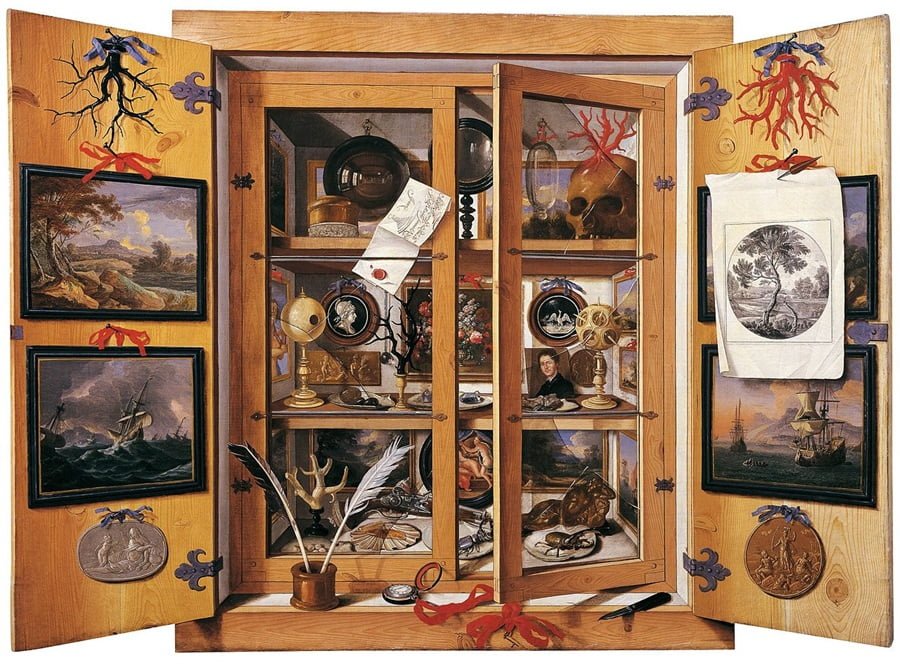

The 1500s was the Age of Exploration, as ships became faster and more efficient, if not necessarily safer. Adventure seekers traversed the world and brought home every kind of curiosity and artifact from distant lands. These oddities were in great demand by collectors, who clamored for the strange, bizarre and unusual, and Cabinets of Curiosity became a focal point in upper class homes.

The Cabinet of Curiosity displayed everything from fossils to strange stuffed animals to tribal masks, and anything else to impress guests and spark debates about the nature of the offbeat items. The more absurd and gruesome, the better.

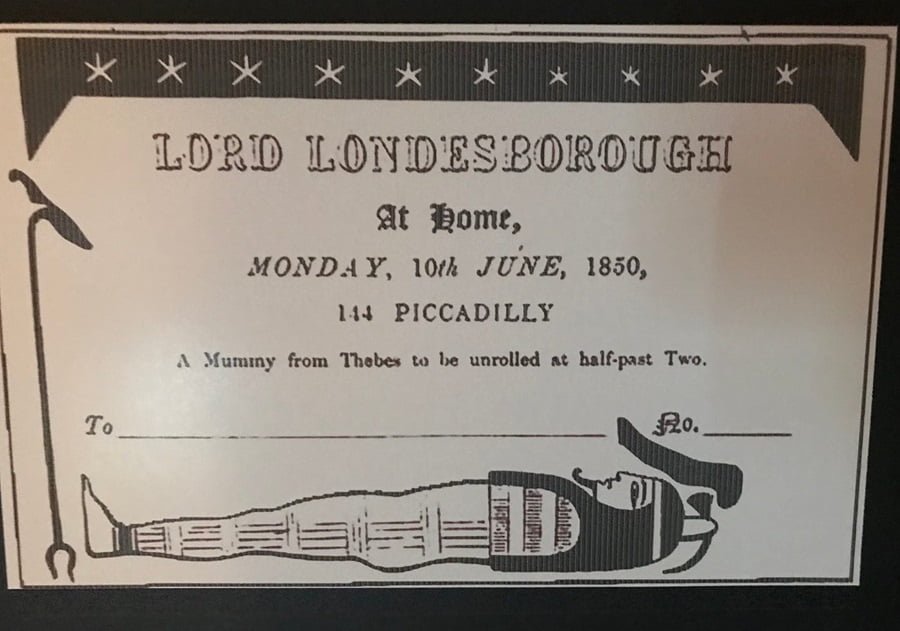

Then in 1798, Napoleon conquered Egypt, and within a few years, his scholarly entourage carried mummies, papyri and other artifacts back to Europe, which were quickly discovered by oddity collectors. The Egyptology craze had begun.

By now, the oddities mania had escalated until a few cabinets no longer sufficed. Entire rooms were converted to private mini-museums through which guests could tour, and everyone who was anyone had to have at least one Egyptian mummy prominently displayed.

Not to be outdone, Americans jumped into the fray and began collecting their own artifacts, including Egyptian mummies.

Those who couldn’t afford an entire mummy had the option to buy a part of one from dealers who specialized in slicing them into their component pieces. Depending on one’s financial situation, a head or limb might be had, or a hand or foot, or just a finger or toe.

Those lucky enough to afford a few complete mummies would have mummy-unwrapping parties.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, European adventurers began exploring the South American continent, where they encountered many indigenous cultures. Among these were the Jivaro peoples of the Amazonian rainforest between northern Peru and eastern Ecuador. One of the Jivaro tribes were called the Shuars.

The Shuars are the famous headhunters often featured in old films. These were the people who decapitated their dead enemies and shrunk their heads. Head shrinking was a long complicated process and I won’t go into the gory details. Once shrunken, the heads were used in various rituals, worn as trophies, and used as a kind of amulet or fetish to ward off evil.

In my research, I was unable to determine exactly who started the macabre trade, but approximately around 1850, a person or persons unknown wanted shrunken heads. The Shuars wanted guns. A bargain was struck. The price was one gun for each head. The heads carried back to Europe and America were a smash hit in the oddities market. The demand soon skyrocketed and other traders jumped in the game.

The Shuars didn’t have a stockpile of heads, and a wholesale slaughter ensued. They began raiding neighboring tribes to obtain heads to meet the demand. Even that wasn’t enough, as was revealed decades later when shrunken heads that had made their way from oddity collections into museums were analyzed. Many of the heads were monkeys and sloths, and some were even women! The shrinking process disguised the features enough to fool the buyers. And as far as anyone knew, women (or animals), had never been used in traditional head shrinking rituals before the trade began.

But it didn’t stop with the Shuars.

Of the several tribes comprising the Jivaro peoples, the Shuars were apparently the only ones who had traditionally practiced head shrinking. But when the Achuar, another Jivaro group, saw the Shuars amassing guns, they weren’t to be left out. They also began raiding other groups to seize heads for shrinking. Soon, they were accumulating their own hoards of guns.

Armed gangs from the two rival tribes began scouring the region for any useable head, terrorizing the tribes and villages which weren’t participating in the ghastly pursuit.

In the 1930s, the Peruvian and Ecuadorian governments teamed up to outlaw shrunken head trafficking. That stopped the carnage in South America, but the heads already in other parts of the world continued to change hands. The United States banned imports of them in 1940, and for a while they were traded on the black market. But interest gradually died down, and today most of the known specimens are in museums or have been repatriated to their countries of origin.

I chose not to add images of shrunken heads to this post for several reasons. Instead, I decided to use pictures representing the curiosity collections that started it all.